Does Practice Improve Musical Memory?

CONSIDER “honing skill” exposure to new information in a disciplined way. Our experience of that exposure is colored by intention — and that intention shapes things like our memory of the process, emotional content during (enjoyment, feelings of progress) — however to our brains, it is nothing more than raw data. Though you may intentionally be practicing scales, you're simultaneously (and usually unintentionally) doing ear training behind the scenes. By default, your brain is acclimating itself to the sound of the scales, growing accustomed to the tonal relationships between notes, noticing the inherent tensions and releases between scale degrees, absorbing the differences in color between keys, and so on.

Consider “technique” and “efficiency” to be synonymous. When you practice technique, you are essentially expanding and improving your muscle memory in such a way that allows you to devote mental energy to the performance of the piece — eg: emotional contours, and musicality — rather than its execution. Having “good technique” simply means that you have the ability to execute physically advanced tasks with minimal effort — technique and expended effort are indirectly proportional to each other, even as the overall materials' difficulty levels rise.

I've learned over my years of teaching that “muscle” memory applies as much to the brain as it does to the physical body. A beginner at walking, for instance, will be completely occupied with the fundamental constituents of walking — stepping, alternating feet, balancing, maintaining forward direction, and so forth. As time goes on, your brain ‘wraps’ around these fundamental processes and automates them, freeing up mental energy for the more complicated tasks. The psychological term for this is ‘chunking’. Do you think about every step you take while walking? Of course not — the process has become automated and you can use your higher brain functions to make sure you don't trip over unexpected deviations in the sidewalk (and if you do by accident, your brain will be able to jump in and compute the quick calculations necessary to keep you from falling over… hopefully).

Having a strong technical foundation allows you to learn things more quickly — in other words, developing muscle memory for something new happens in a shorter amount of time. Something “hard” to play is often merely a conglomerate of more basic, fundamental techniques. For example, upon first attempt there might be a particularly hard passage of notes to play — however upon analysis and dissection, it is realized that the notes comprise a mixture of scaler and arpeggio‐like motion. Now the muscle memory from having practiced scales and arpeggios in the past can get put to immediate use without any conscious effort on behalf of the player. Your brain automatically realizes that the seemingly new passage you are attempting to play consists of pieces of material with which you are already familiar.

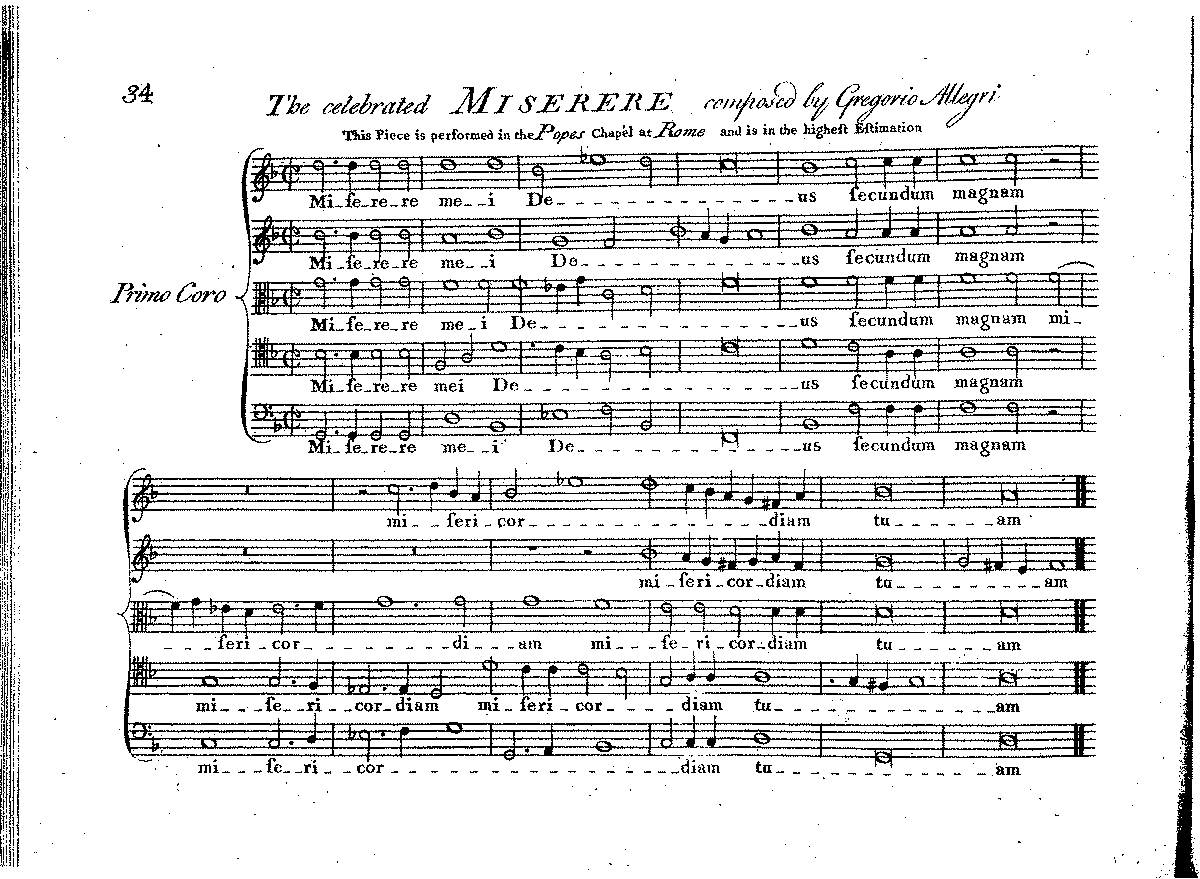

Expanding on this idea, consider the concept of fidelity — the longer the exposure, the finer the resolution. Legend has it that Mozart had an almost miraculous musical memory, allegedly having memorized an entire piece after just one listen (Gregorio Allegri's “Miserere” — see sheet music below). If I listened to an unfamiliar symphony by Mozart later today, I might be able to sing back one or two of the main themes as they are the ones that would have the most presence throughout the piece, and therefore be easiest to memorize. Now let's say I spent the next year listening to and composing symphonies on a daily basis. By the end of that year, the fidelity of my ‘symphonic comprehension’ would be at a much higher resolution, and at a much greater depth, thereby rendering the “main melodies” of a symphony I've never heard before easy to memorize, almost even automatic. My brain and its higher cognitive functions would be relieved of bigger‐picture duties, left free to focus instead on the finer details of the symphony. I would at this point theoretically be capable of saying something like, “Remember the short oboe passage towards the middle of the second movement that mimicked the second violin? It was beautiful!”

Practicing pieces, songs, tabs, learning other players' solos, etc, is exposure to nuance, thereby familiarizing your brain, ear, and fingers with that more detailed information. Your physical proficiency at the instrument increases, as does your ability to improvise.

Your ear gets better as its able to recognize harmonic and melodic information more quickly and accurately. Your ears, connected to your body, eventually allow you to think through your instrument, as if the instrument and body merge into one. Music reading improves — you can take in new passages more quickly, and play them better in less time. Sight reading improves (the ability to play a piece while looking at it for the very first time). You are able to memorize larger and larger sections of music in less and less time. Eventually, one automatically memorizes pieces solely by learning how to play them. Finally, all these aspects can be said to come together as the sum total of one’s innate musicality.

Simplicity, for me, is best characterized in a story from the art traditionally the favorite of mathematicians and scientist: music. When Mozart was fourteen years old, he listened to a secret mass in Rome, Allegri's Miserere. The composition had been guarded as a mystery; the singers were not allowed to transcribe it on pain of excommunication. Mozart heard it only once. He was then able to reproduce the entire score. Let no one think that this was exclusively a feat of prodigious memory. The mass was a piece of art and, as such, had threads of simplicity. The structure is the essence of art. The child who was to become one of the world's greatest composers may not have been able to remember the details of this complicated work, but he could identify the threads, remember them and reinvent the details having listened once with consummate attention. These threads are not easily discovered in music or in science. Indeed, they usually can be discerned only with effort and training. Yet the underlying simplicity exists and once found makes new and more powerful relationships possible.